When Purpose Becomes a Brand Asset (and Nothing More)

Originally published on Medium.

Photo by Amanda Kloska on Unsplash

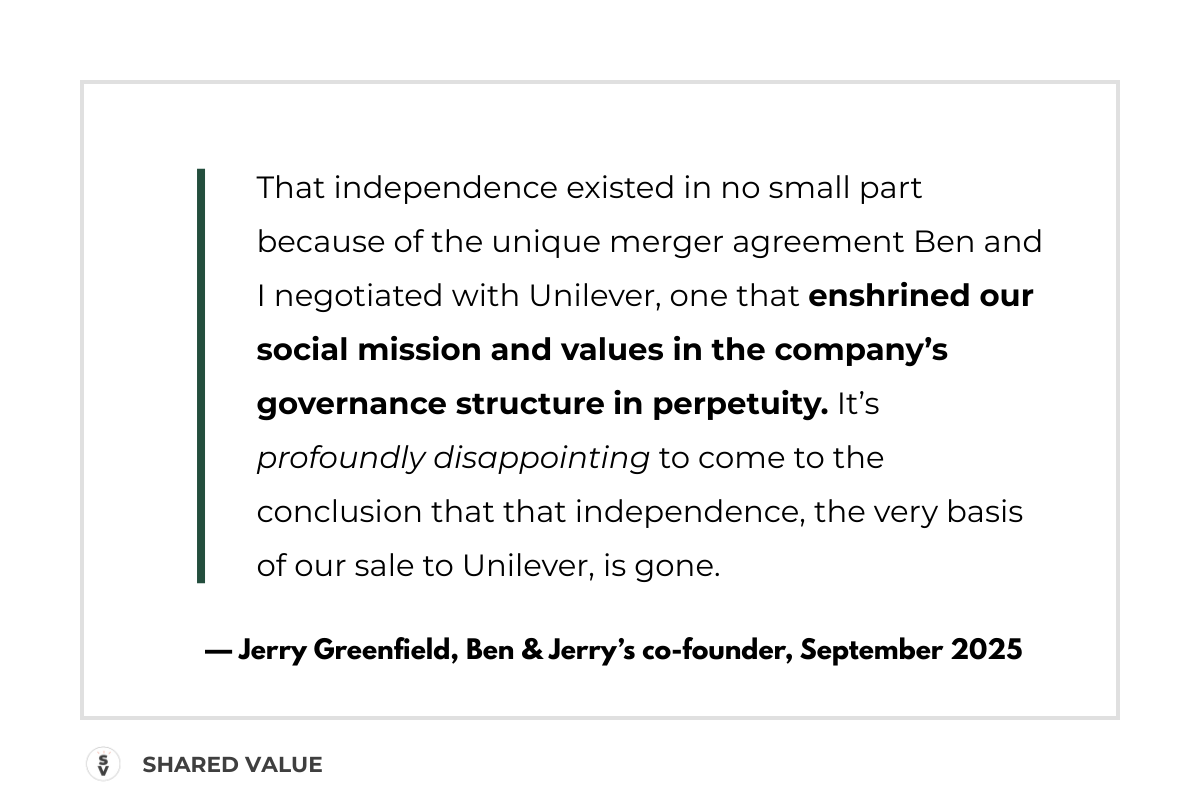

Jerry Greenfield just resigned from Ben & Jerry’s after 47 years, stating: “It’s profoundly disappointing to conclude that that independence, the very basis of our sale to Unilever, is gone.”

What Purpose-Washing Actually Looks Like

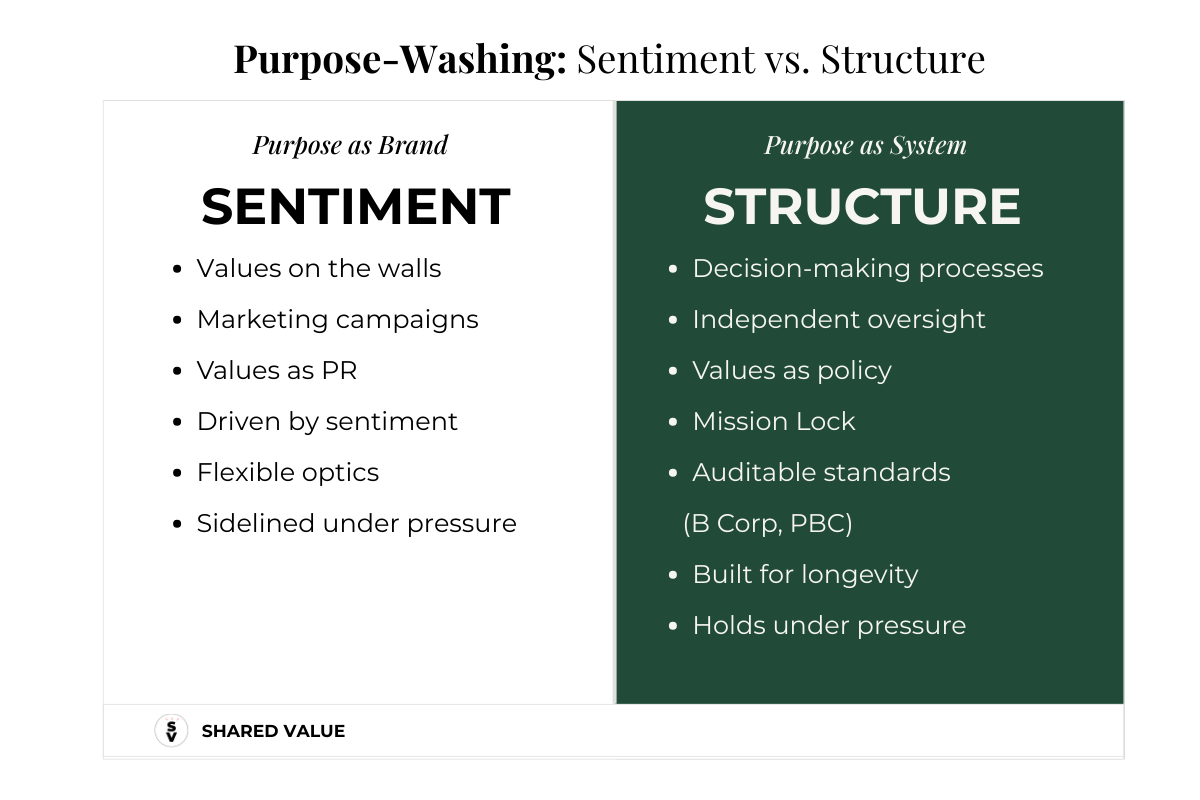

Purpose-washing isn’t just corporate hypocrisy. It’s a failure of organizational design.

It’s treating purpose as a marketing asset instead of an operational system. It’s posting values on walls but not embedding them into decision-making processes. It’s the gap between public commitments and internal practices; a system that prioritizes shareholder returns above all else, packaged in stakeholder-friendly language.

We see it when companies quietly roll back sustainability initiatives during budget constraints. We see it when organizations restructure to eliminate thousands of jobs while doubling executive bonuses. These aren’t just difficult decisions. They’re design choices that reveal what’s truly prioritized when trade-offs become unavoidable.

Purpose-washing runs on sentiment and aspiration. Authentic purpose runs on governance.

Press enter or click to view image in full size

The two faces of purpose: sentiment vs. structure.

Why This Case Matters

This quiet erosion of stakeholder governance is why the Ben & Jerry’s story is such a critical warning. Their independent board structure and merger protections were designed as a blueprint for stakeholder accountability. Structural safeguards for mission integrity.

Authentic purpose isn’t maintained through good intentions alone; it requires real accountability. This is why certifications like B Corp status and legal structures like Public Benefit Corporations exist. They create documented, auditable standards that make purpose more than just marketing copy.

Ben & Jerry’s was designed from inception as a vehicle for social change through business. When Unilever acquired the company in 2000, the founders negotiated what you could call “mission lock.” An independent board with legal authority to challenge corporate decisions, even to sue Unilever if they broke the agreement. Over time, Unilever slowly stripped away the board’s authority, particularly when activism became politically uncomfortable. In 2021, when the board voted to cease sales in Israeli-occupied territories, Unilever bypassed them entirely by selling the Israeli business to a local licensee. By 2022, Unilever was removing Ben & Jerry’s CEO without board consultation. A direct violation of merger terms. The board sued, but by then the damage was clear: even the strongest mission lock wasn’t enough when the parent company decided to override it.

Steve Liss/The LIFE Images Collection via Getty Images/Getty Images

If the most structurally protected mission-driven brand couldn’t maintain alignment, what does that mean for everyone else? Values are easy to market but harder to defend when living those values costs money or creates friction. Even robust legal agreements can be circumvented when power imbalances are significant enough.

Press enter or click to view image in full size

Moving Forward

Purpose isn’t what organizations print on packaging or post on websites. It’s what they’re structurally designed to protect when protecting it becomes difficult.

It’s not the mission statements or marketing campaigns. It’s the structural mechanisms that hold leaders accountable when sticking to the mission gets inconvenient.

The question for any mission-driven organization isn’t whether they’ll face pressure to compromise their values. It’s whether their governance structures can maintain mission alignment when that pressure arrives. Ben & Jerry’s had some of the strongest protections ever negotiated, and even those weren’t enough.

This doesn’t mean mission-driven business is impossible. It means we need better frameworks, stronger enforcement mechanisms, and more sophisticated approaches to stakeholder accountability. In my work with mission-driven companies, I’ve seen this pattern play out across industries: when growth pressures intensify, the guardrails give way unless they’re actively defended.

Because at the end of the day, there’s a difference between a brand asset and a business system. If even Ben & Jerry’s couldn’t hold the line, what chance do companies without guardrails have?

This piece is part of my ongoing exploration of how we protect integrity in business.

If it resonated, subscribe to Shared Value for more essays, frameworks, and tools at the intersection of governance, B Corps, and the future of business.